I woke up this morning to sun coming in the window, and I felt joyful. Another day for a long walk with my husband, Andy, and my little dog, Rafi. Rafi was recently restored to good health and puppy-behaviors (even tho he’s ten years old) after six months of baffling pain, so I’m pretty joyful about that as well. None of us has coronavirus, and we are fortunate that we can just stay home. Both of my sons and their wives work at home — and my grandson is home-schooled. So there’s that.

But then I paused for a moment in my reflections and happy feelings and thought of how an observant Jew might begin the day, with this prayer:

I thank you, living and enduring King. You return my soul to me with compassion. How great is your faith (in me)!

מוֹדֶה (מוֹדָה) אֲנִי לְפָנֶֽיךָ מֶֽלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּים. שֶׁהֶֽחֱזַֽרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי ,בְּחֶמְלָה. רַבָּה אֱמֽוּנָתֶֽךָ׃

Modeh (Modah) ani l’fanecha, melech chai v’kayam, she-hazarta bi nishmati b’chemla. Rabba emunatecha.

The prayer is followed immediately with the first blessing of the day recited with the first action of the day after rising, hand-washing:

Blessed are you, O Lord, our God, King of the Universe, who has sanctified us through your commandments and has commanded us concerning the washing of hands.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה הָ׳ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדַיִם

Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu melech ha-olam asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al netilat yadayim.

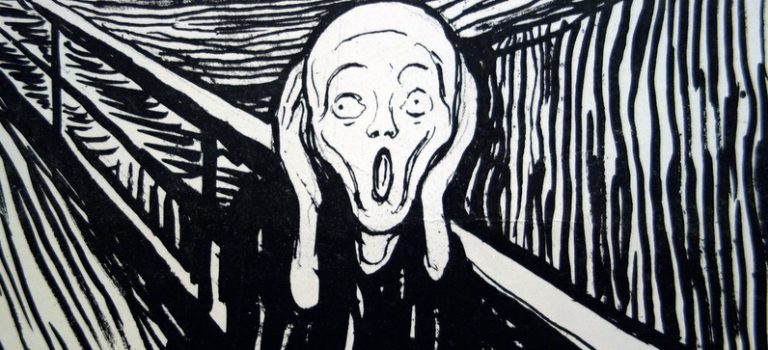

For many of us, reciting a structured prayer followed by a specific action and structured blessing might be problematic. Why not just relax in the moment of joy on waking? Do or say something spontaneous? Surely that’s more “authentic.” But perhaps there’s something to be said for managing our “mood” and shaping our worldview.

Here are some things that come into my mind and heart as I contemplate this prayer of gratitude and the first blessing of the day.

Modeh (modah) ani l’fanecha – I thank You, I am grateful before You. My awareness on waking is immediately directed beyond myself, though it includes myself, as I express gratitude…

Melech chai v’kayam – Living and enduring King. Despite what appears to be reality from our limited point of view, there is a greater reality in which All That Is lives and breathes and “endures,” is eternal…

She-hazarta bi nishmati – You return my soul to me. The breath of that greater Being-ness, of All That Is, reanimates our consciousness, our awareness of being…

B’chemla – With compassion. The very nature of all being is compassionate and the fact that we are here, that we have consciousness, is evidence of that…

Rabba emunatecha – How great is your faith (in me)! “in me” is added in the translation as an assumption since the conversation is about returning spirit or consciousness to the one reciting the prayer. But what if that faith is more universal? What if that faith is in All That Is, in the processes of creation as well as the Being-ness of what is as of yet uncreated? Faith in us but in so much more, in that of which we are all part…

So as we take our first breath, instead of focusing on our personal and particular blessings — or getting lost in what we feel we are missing — we turn our attention to the greater whole of which we are a part, to the inherent compassion of the whole and for ourselves in particular as we once again come into being, into consciousness.

And now, restored to the created world and remembering we are part of All That Is, celebrating our unique ability to be conscious of our connection, we take our first step into the day. We wash our hands.

Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu melech ha-olam – Blessed are you, O Lord, our God, King of the Universe. Again, our attention and awareness are directed to All That Is, reminding us we are part of that and not isolated from it. We are not alone. We are part of a living, breathing, compassionate whole. And we are conscious of that, reminding ourselves of our consciousness and our role in creation through the act of saying a blessing…

Asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav – Who has sanctified us through your commandments. Imagine that! That which is so much greater than we, All That Is, “sanctifies” us, a part of the whole. First reminded we are part of an eternal wholeness, we now recognize we are simultaneously “sacred” or set apart from it. Or perhaps better, we are unique within it, and we have special responsibilities within it. Our responsibilities, those things we are commanded to do to fulfill our nature, are what sets us apart…

V’tzivanu al netilat yadayim – and has commanded us concerning the washing (lifting) of hands. The blessing now specifies the commandment we are recognizing and performing, our special obligation. Translated “washing,” netilat literally means “lifting.” We are first singled out from All That Is with commandments that allow us to fulfill our unique nature as human beings and as Jews. Then in performing the commandment we single out a part of ourselves, our hands, sanctifying them with water and lifting them to the heavens.

Think about this for a moment. The first action of the day, sanctifying our hands, setting them apart. There is a depth and diversity of symbolism here, something we can all meditate on, finding our own meaning.

But there is more. God — All That is — the greater Whole — within which we all are born, live our lives and die, compassionate infinity, makes conscious choices, first of us, setting us apart by giving us commandments, then in particular of our hands. There is a reason for this, a meaning in it.

And so with our first prayer, we recognize the compassion that has granted us another day of neshamah — breath, consciousness, a uniquely human consciousness. Then as we wash our hands and lift them, we recite the blessing that invokes our human uniqueness that can “reflect on and celebrate itself in conscious self-awareness.” (The Dream of the Earth, Thomas Berry, Sierra Club Books San Francisco, 1988, p. 132). And from that mental and spiritual space, we begin our day.

It’s still wonderful to wake up in the morning and feel happy because of my particular blessings, my family, my little dog, our home, our health, a relatively warm and sunny day. But this Jewish beginning, a formulaic prayer followed with a ritual action and the first of many berachot, blessings, centers me in a framework of meaningful action. And it does that even on the days it’s raining or hardships cause stress or sadness.